The International Rescue Committee conducted two mortality surveillance projects using  community health workers who visited homes and collected vital events data with mobile phones. The project in Sierra Leone was completed, but the project in DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo) was interrupted because of rebel conflict.

community health workers who visited homes and collected vital events data with mobile phones. The project in Sierra Leone was completed, but the project in DRC (Democratic Republic of Congo) was interrupted because of rebel conflict.

In both Sierra Leone and DRC, it is extremely difficult to obtain acurate mortality counts. Many children die before their fifth birthday. In Sierra Leone, malaria, diarrhea and pneumonia account for the majority of deaths in the under-five population. Many of these deaths are not detected by the government agencies. The IRC wanted to initiate a program to better collect, record and collect vital event data. This would happen with better training, better  equipment and better guidance.

equipment and better guidance.

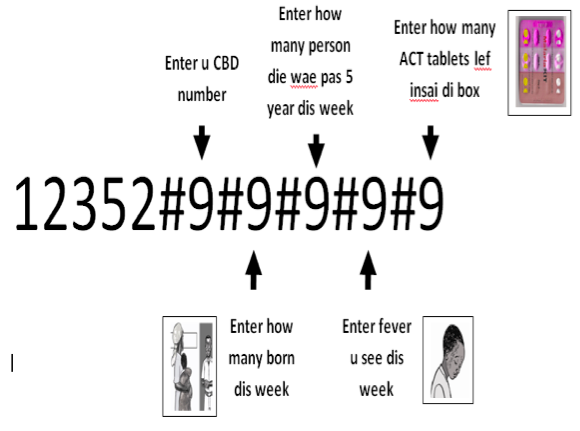

The overall objective of the studies was to evaluate the effectiveness of a using mobile phones to document vital events by community health workers who were to report on all deaths, births, and childhood illnesses. Results were to be analyzed against a pre- and post-program census. Initial household census counts were done using a questionnaire that detailed household members, sick child treatment behavior ahd migration information. Then each week the community health workers documented births and deaths using mobile phones.

The results of both studies was encouraging. The completed study in Sierra Leone showed the following results:

- Weekly reporting percentage averaged 93% over the course of the twelve month project.

- Power sources for phones and supervision were key challenges for data reporting.

It was thought that the community health workers were a good choice to use for this project. They were well-respected, knew the population and understood the difficulties involved. Also, in the DRC, they were considered humanitarians and therefore not targeted in rebel conflict.

Many health workers already had mobile phones, or at least were familiar with them, so there was no issue of learning a new technology.

There were however some concerns about phones being lost or stolen and solar chargers not working. Some of the health workers had to walk long distances (3 hours or more) to charge their phones and this often presented a problem.

Paul Amendola concludes in his report,

” The project, aside from the calculation of mortality surveillance, has increased the overall knowledge of mobile phone-based reporting data. The high reporting rate suggests that collection of data, even from rural, low-resource areas, is feasible, and can be reliable. There were certain programmatic and reporting considerations that need to be included into future projects that will help enhance the reporting and allow for lessons learned. Solar chargers, and the unreliable power supply in developing areas continue to be a component of mobile-reporting that needs to be explored.

Mr Amendola goes on to say,

“Prior to project initiation, the IRC technical unit did not have any mobile phone-based collection projects. As a direct result of this project, there are currently 31 mobile based data collection projects in place. There were a lot of lessons learned from this project – challenges of supervision, solar chargers, and clear reporting areas, but the overall effect of the development will have, and has already had a positive effect on additional projects.”

I had the great pleasure of interviewing Paul Amendola who was there during the study. In the following video, Paul gives us his personal thoughts on the study – the challenges, the opportunities and the bright future of using mobile in global health.

To read other posts in this exclusive ongoing series, please visit the Mobile Health Around the Globe main page. And if you have a Mobile Health Around the Globe story to tell, please post a comment below or email me at joan@socialmediatoday.com Thanks!

source: Amendola, Paul, IRC, MOVERS Final Report, November 2012

Video Transcript (by TranscriptionStar)

Joan Justice: Hello I’m Joan Justice with HealthWorks Collective and I’m here today with Paul Amendola from the International Rescue Committee. I asked Paul to come and talk with me and give me his personal comments about this IRC project in Africa using mobile phones to track mortality. Paul, why don’t you tell us just briefly about the study and then some of your personal thoughts on the results and what this means for the use of mobile and healthcare in the future?

Paul Amendola: Thanks Joan. We are two primary projects, one in Sierra Leone and one in the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Sierra Leone we were using community health workers to send in reports on mortality and treatments weekly via SMS and in Congo it was a similar project. We were using community health workers or their version of community health workers to send in reports on mortality again with mobile phones over SMS. Basic messages, basic phones but data that is really hard to get and data we can use in real time.

Joan Justice: And what was so difficult before in getting this data? Why did you start using mobile phones?

Paul Amendola: Mortality is a hard thing to… is a very difficult… its difficult data to get. Normally it takes a really large survey covering a large area, with a lot of technical support, it’s very expensive, it’s very hard to do. So the thought’s been moving away from mortality studies and mortality surveys to more prospective mortality surveillance and using mobile phones was a way to get that data and to someone who could use it and analyze it in real time.

Joan Justice: Okay great and what are your… what were the results and thoughts on this study from the standpoint of the IRC?

Paul Amendola: The biggest result for both of the studies was the reporting rate, both studies were focused on very rural areas both of Sierra Leone and of Congo and the reporting rate for one project was 93%…

Joan Justice: Yeah, I saw that.

Paul Amendola: And in any other project it was 100%. Roughly 50 community health workers in each project and in really rural areas where it takes a long time normally to get it stated in. So even though there were challenges along the way, we were able to get valid accurate data weekly for the projects and what it means for IRC it terms of the results is we can get, we can do similar project relying on community health workers in similar areas. A lot of the things we thought were not going to be possible, really would be possible. In terms of literacy, both areas have very little literacy but that doesn’t translate to numeracy as well. There were some examples in Sierra Leone where we were doing a training and the community health worker was filling in an exercise sheets of exactly what we wanted them to send which SMS to send into us. And they couldn’t write down the message they were sending but when they were given a phones they could type it in.

Joan Justice: That’s interesting.

Paul Amendola: Yeah, so all these barriers we thought were there, there were solutions for.

Joan Justice: Yeah that’s great and you were there, what did the people think about the study when they were doing it, the community health workers?

Paul Amendola: It’s interesting and in both places it was a little different. In Sierra Leone where there’s already mobile phones, they are very prevalent; they thought we should have been doing this since the beginning. They were a lot more comfortable than the paper based forms and just their knowledge of the mobile phones and how the mobile phones were working was amazing. We did feasibility studies of where there was mobile coverage for some of the areas and there were some villages that we didn’t think had any mobile coverage at all and they wouldn’t be able to send their messages, but somewhere in the village, there’s just one example, you need to go to go to a certain mango tree and hold the phone up against the mango tree and it was just enough signal to send an SMS.

Joan Justice: That’s amazing.

Paul Amendola: Yeah and we were able for the rest of the project to get this data in from that village. In Congo it was a little bit of a different story, there was the mobile phones… this was an introduction of a new technology so was the… the training was a lot more intense, the uptake and the refresher training and the support needed more time.

Joan Justice: But the community health workers were the people to choose for this kind of task you found that out?

Paul Amendola: Yeah that’s what we were looking at too for mortality surveillance, is the community health worker the right person to be sending in this data? And with both projects it’s allowed us to expand mortality data to start receiving treatment data and stock out data as well.

Joan Justice: Okay so this has opened the way, paved the way for future studies, there’s going to be a scale up?

Paul Amendola: Yeah both, future studies and scale up. In Sierra Leone in the midterm evaluation we having them initially send in four data elements every week and we were able to scale up to eleven for the second half of the project with the reporting rate and the accuracy rate still the same.

Joan Justice: That’s really great, so what do you think, what would you say are the implications of mobile health going forward?

Paul Amendola: I think it’s showing you how challenges such power sources and mobile coverage and literacy aren’t really barriers for mhealth in rural areas of Africa. In Sierra Leone we were… in both places keeping the phones charged and keeping the phones working was a challenge but in Sierra Leone when solar charges weren’t working, the community health workers as a group devised a plan to use credit that was given to the phones to pay a shopkeeper to charge their phones so no money had to be exchanged. We could send their credits from the headquarters office and it allowed the project to go on so there are solutions, there are solutions to the problems.

Joan Justice: That’s really wonderful Paul, thanks so much this is really I think a great step forward for mobile and for global health and thanks for bringing this study to our attention and for being here with me today. I appreciate it.

Paul Amendola: Thank you.