I spend a lot of my time reading, thinking and writing about politics and medicine. I love the debate. Three of the five Kirsch progeny engaged in serious school debate programs, and I believe that they received years of training at our dinner table. I certainly learned a lot from them – and still do – and I hope they picked up a few worthy lessons along the way.

I spend a lot of my time reading, thinking and writing about politics and medicine. I love the debate. Three of the five Kirsch progeny engaged in serious school debate programs, and I believe that they received years of training at our dinner table. I certainly learned a lot from them – and still do – and I hope they picked up a few worthy lessons along the way.

Some time ago, an associate admonished me to avoid dialogue concerning religion or politics, two of my staple conversation themes. This advice seemed misplaced as I’ve never had an argument in my life discussing a controversial issue. Indeed, I seek out these opportunities. I don’t want the other individual to change the subject; I want this person to change my mind.

Controversy erupted recently when Hepatitis C enthusiasts pushed back against the U.S Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) draft recommendation regarding testing folks for hepatitis C virus (HCV). More turbulence is sure to follow. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had previously issued their guideline advising that all individuals born during 1945-1965 be tested once for HCV. That would include the Whistleblower who has no risk factors associated with HCV infection. I have not been tested and have no intention of doing so.

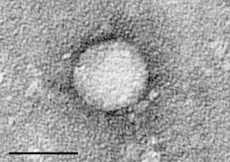

Electron Micrograph of HCV

I’ve already posted a vigorous rant explaining why I feel that patients with HCV are overtreated. As I indicated there, the Food and Drug Administration has approved two new medicines, boceprevir (Victrelis) and telaprevir (Incivek) which have significantly increased treatment efficacy. HCV patients who opt for treatment are prescribed one of these two medicines along with two others to complete a three drug HCV cocktail. These are very serious medicines with potential serious toxicities.

I applaud this medical advance and hope that research in the near term will increase efficacy, reduce toxicity and simplify the treatment.

HCV experts and many physicians advocate treatment to eliminate the virus so that the hepatitis infection will not progress to cirrhosis and liver cancer. Liver failure from HCV infection is a major cause of liver transplantation.

Indeed, if you were a HCV patient and your doctor advised treatment “to prevent liver failure, cirrhosis or liver cancer”, I suspect you would be inclined to accept the recommendation. I don’t think, however, that many patients are given the fair and balanced context when they are considering how to proceed. Only an informed patient can provide informed consent.

Consider the following before pulling the treatment trigger.

- The vast majority of HCV patients have no symptoms and have had the disease for decades.

- Only 10-20% of HCV patients will develop cirrhosis, many of whom will function well.

- The treatment is toxic and extremely expensive.

- We have no reliable method to determine which HCV patient is destined for future complications.

- HCV patients who ‘respond’ to treatment may have lived a normal life without treatment.

Is there a role for treatment in this disease? Of course, but I suspect that once again, medical practitioners are casting too wide a treatment net ensnaring many folks who should be left alone.

The USPSTF just issued their draft HCV guidelines that were considerably narrower than those of the CDC. The task force recommends HCV screening only for those who are at high risk of the disease, such as those who used intravenous needles or received blood transfusions prior to 1992. Unlike the CDC, no mandatory screening of folks born during 1945-1965 is advised. The task force pointed out the absence of proof that widespread screening for HCV would reduce liver disease and mortality.

When the final guideline emerges, there will be criticism. Some of it may be based on the medical merits, which is fair game. Other criticism will try to game the system. There’s a huge and growing HCV testing and treatment industry and gazillions of dollars at stake. Certain stakeholders will advocate policies that endorse widespread screening for HCV. Will this be only for medical reasons? Our track record on this issue isn’t encouraging. Beware of conflicts of interests buried under feigned arguments to protect patients. There are 4 million Americans with HCV. Treatment with the new 3 drug regimen can cost in excess of $50,000 per patient. Do the math.

50,000 x 4,000,000 =

We shouldn’t retreat from discussing whether treating HCV makes sense. After all, it’s not religion or politics.