Understanding the revenue cycle can be tricky for many of us who work in healthcare. Unless we are directly involved with patient accounts, the subtleties of the process may be lost on us. That is, until we find ourselves patients – at which point even the most minute details of the process evident to us.

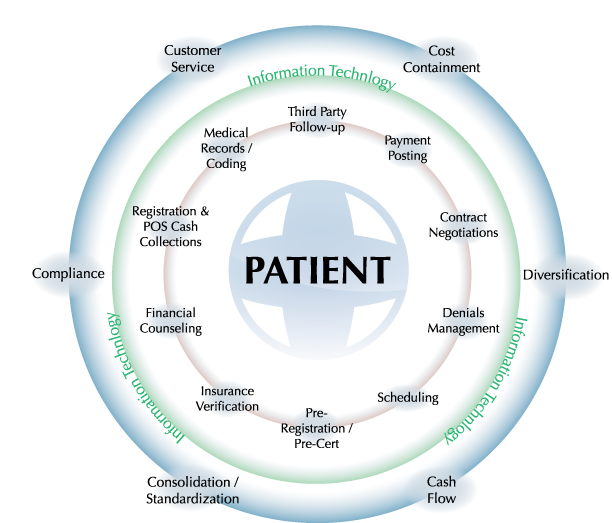

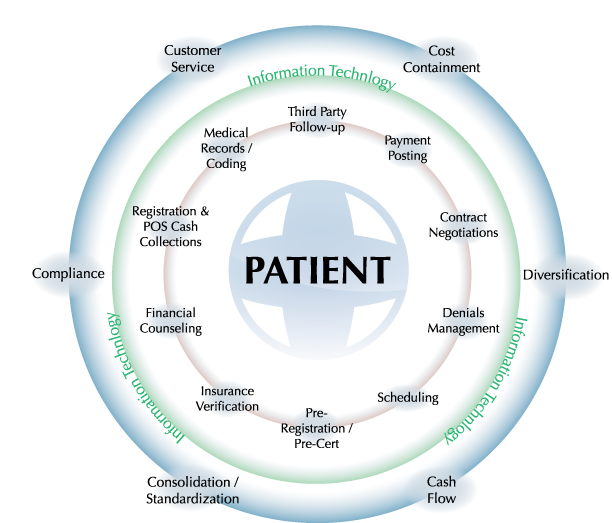

If we want to get a clear view of the process in its entirety, and how we can improve at each step of the way, it’s often easiest to look at it as a continuous process which is always initiated by patient registration.

Understanding the revenue cycle can be tricky for many of us who work in healthcare. Unless we are directly involved with patient accounts, the subtleties of the process may be lost on us. That is, until we find ourselves patients – at which point even the most minute details of the process evident to us.

If we want to get a clear view of the process in its entirety, and how we can improve at each step of the way, it’s often easiest to look at it as a continuous process which is always initiated by patient registration.

As you can see, the circular nature of the process means that, in some cases, many claims on a single patient may be in different points in the process simultaneously – so, coordination and communication between those dealing with the claims, the physicians, the coders and, in many cases, the patients themselves, is critical.

The process may begin with registration, but the wheels really begin to turn during the encounter, wherein the physician is making ample notes regarding the nature of the visit, the procedures or tests ordered and will be prepared to document after the encounter is finished. It is during the physician’s initial documentation that the process begins to take shape: the way that the physician documents will directly affect how the claim is to be coded. EMRs, ultimately, should make it far more likely that a physician will document correctly nearly all the time, preventing coders from needing to ask them for clarification on a diagnosis.

By the time the coders have begun coding an encounter, the patient has settled into the next phase of treatment – home, long term care, etc. and the next communication they receive will likely be in regard to payment. Coders work to the top of their expertise to code many charts a day – a percentage that is in line with however many discharges there were the previous day- and to code many charts efficiently and accurately is tough enough without being bogged down by physicians who routinely create poor documentation.

By making use of the wiles of the electronic medical record, a physician may be able to save a lot of work down the road for both themselves and the coders. Refusal to do this or stringent adherence to “old ways” will only impede the process.

But, eventually, the chart is coded and will make its way beyond the department of health information and find itself ready to be submitted. When patient accounts have taken over control of the chart, it becomes less and less a picture of the patient’s health record and more of a tab for the hospital – by this stage in the process, the patient has been greatly reduced to a set of neat numbers, both monetary and through the medical coding. Throughout the next phase it will come up against third party payers who may disagree with the charges, claiming that a patient received care that they did not need -and therefore should not be paid for – or there is some other error within the coding that needs mending before it can proceed.

It is also during this time that financial counselors may be reaching out to patients, if they have not already, to discuss payment plans and options, hopefully solidifying some form of payment from the patient to the hospital directly. If this does not occur, the claim will eventually be taken off the hospital’s plate and left to a collection’s agency- which is not the happiest end to the process for anyone involved. Otherwise, we would assume that the claim is paid by the patient and the cycle simply begins again with new patients.

While there is quite a lot to the process of the revenue cycle in a hospital setting, it would seem that an awful lot of it is common sense: the flow is intuitive and makes sense in the setting. It’s also easy to identify areas which may be of weakness in your organization.

Review the cycle above and ask, “What are areas in my revenue cycle at my organization that are weak, or could stand to be improved upon?”