Steve Blank is known for informing entrepreneurs that, “The safest bet about your new business is that you’re wrong.” He contends, “A startup is not about executing a series of knowns. Most startups are facing a series of unknowns — unknown customer segments, unknown customer needs, unknown product feature set, etc…”

Steve Blank is known for informing entrepreneurs that, “The safest bet about your new business is that you’re wrong.” He contends, “A startup is not about executing a series of knowns. Most startups are facing a series of unknowns — unknown customer segments, unknown customer needs, unknown product feature set, etc…”

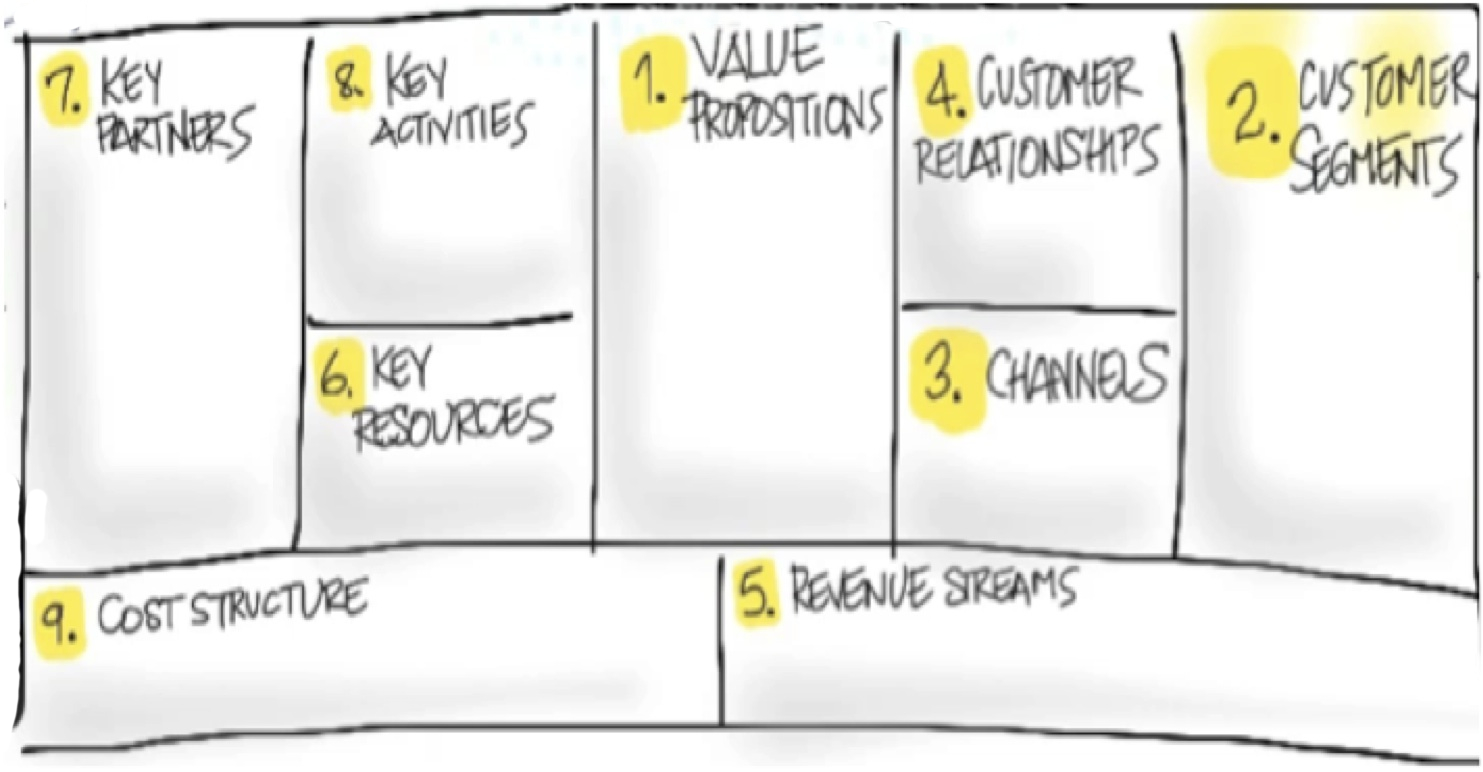

As a serial entrepreneur, academic, veteran, author and one of Forbes 2013 30 Most Influential People in Tech, Blank has carved out a well-documented career teaching others success in the startup world using his Lean LaunchPad curriculum. At its core, the Lean method teaches innovators that: 1) startups are not smaller versions of large companies. This means startups need different tools than those used in existing companies, and 2) there are no facts inside of their building. Therefore, they need to get outside to test whether their hypotheses are correct.

It’s a big idea – one that in 2011 caught the eye of the federal government, a prominent backer of technical innovation and the country’s second-biggest leader in research and development funding. The theories were so highly regarded, it led to an unlikely partnership with the National Science Foundation (NSF), the $6.8 billion government agency that supports research in all nonmedical fields of science and engineering. And, while many argue that inefficiency, redundancy and regulatory burden of government agencies can hinder innovation, the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) offices at the National Institutes of Health(NIH) and the Department of Energy (DOE) have also partnered with Mr. Blank to incorporate his methodology into their agency practices. Can Federal Agencies Be “Innovative”

Can Federal Agencies Be “Innovative”

NSF requested Mr. Blank modify the Lean LaunchPad course he developed at Stanford to a curriculum for the NSF’s Innovation Corps (I-Corps). The first fruits from this cross-pollination with the NIH came in October with the launch of the pilot I-Corps at NIH program, concluded this week with final presentations.

The National Cancer Institute is participating in I-Corps at NIH through the SBIR and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) Programs along with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The institutes have jointly sponsored 19 teams ranging from therapeutics to medical devices, hoping that the companies can change the world by bringing their research from laboratories to patients in a cost-effective and efficient manner.

“The SBIR Programs have a unique role in the federal government fostering small businesses and investing in early stage research,” said Michael Weingarten, NCI SBIR Development Center Director. “Together with I-Corps, the SBIR Programs have an opportunity to take our efforts to the next level and provide our companies with the tools to develop medical technologies faster, better and with greater success.”

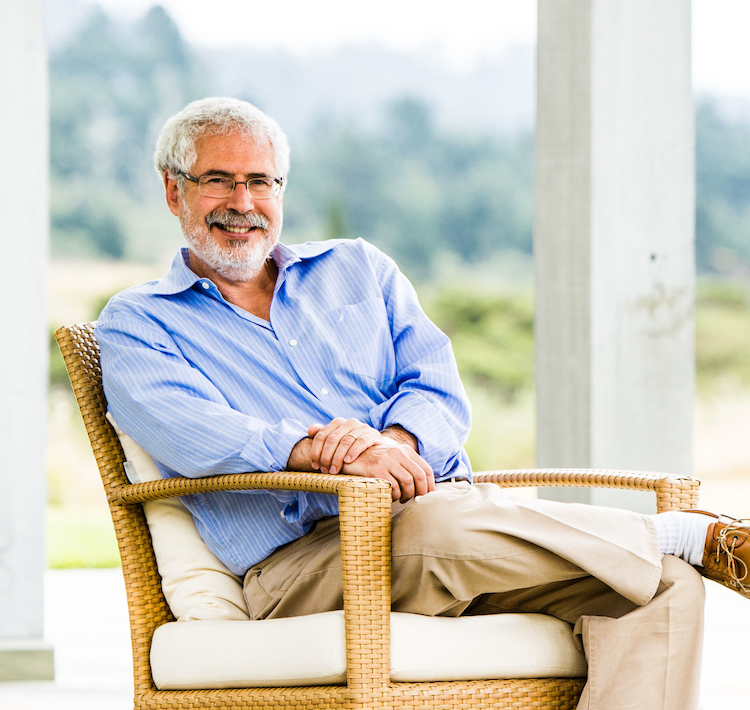

The NIH SBIR/STTR Programs serve as an engine, helping small businesses develop the next generation of medical technology breakthroughs, while also filling a critical funding gap in early stage research and high risk technology development. The Center also recently led a matchmaking effort (NCI SBIR Investor Forum) to bring together investors, strategic partners, and the most promising NCI small business awardees developing targeted cancer therapies, diagnostics, and medical devices.

According to the NCI SBIR Program I-Corps coordinator, Christie Canaria, PhD, “All the teams selected are already funded companies that have received an NIH SBIR Phase 1 Grant through an extensive peer review process by industry experts. This I-Corps pilot initiative is part of a suite of targeted efforts by the NCI SBIR Development Center and other programs across NIH to go beyond funding to help accelerate the translation of research concepts into technologies that will improve patient care.”

When asked how his first cohort of students at NIH compares to his Stanford students, Mr. Blank laughs and tells me they are remarkably similar. “All the teams came in lacking a link between an idea and making an actual company,” he says. “Most often, the idea is a small part of the overall company. That’s what has been screwed up with the last 30 years of grant funding. A good idea is not going to help anyone unless it succeeds in getting to the commercialization stage .”

Blank observed, “By the end of the class the 19 NIH teams spoke to 2,120 customers, tested 695 hypotheses and pivoted 215 times. That’s an amazing amount of work . We’re proud that each and every one of the teams left the program with evidence, urgency and velocity they didn’t have coming into the class.”

The I-Corps Approach

Blank asserts that the current medical school curriculums and grant funding cycles are more focused on the science than the business sense and methods of starting a successful company. “I-Corps provides an efficient way to teach the teams working with the government the distinction between an idea and a company.”

As in the Lean LaunchPad for Life Sciences pilot course at UCSF, I-Corps teams learn how to define clinical utility, understand customers and recognize downstream commercialization. The primary difference is that most NIH participants are already well-accomplished experts in a particular field. Dr. Hobart Harris, Chief of General Surgery at UCSF, was in the first UCSF cohort, and claims his business could not have succeeded without lessons in bringing his, “idea to the marketplace,” and that is exactly the model being replicated at the NIH.

Using a nine-week course that ended with final team “Lessons Learned” presentations this week, Blank is working with business experts and NIH SBIR officials to help the teams explore potential markets for their federally supported technologies in development. The course began with a three-day “Entrepreneurial Immersion” Blank describes as, “A real eye opener. They struggled to tell what business they were in on day one. Instead, they would describe what they were making. By day three we got almost all of them able to articulate what problem they were solving and for which users.”

At completion, the companies have each engaged with 100 potential customers and he claims, “Regulation, reimbursement, clinical trials, potential partners and intellectual property (IP) are all top of mind now.” However, he also says that his greatest hope for next steps not only includes more cohorts of companies that go through NIH I-Corps and DOE’s Lab-Corps, but also with curriculum for medical schools and large research centers with life science communities. Who Is Learning From Whom

Who Is Learning From Whom

Although Blank’s methods have proven effective for startup companies in various sectors worldwide, his theories on how to take companies to market product improvement and commercialization, is a different and untested challenge within the government. Until now. This new I-Corps model is about making a viable business, which is a necessary step to ensuring that patients – taxpayers – will ultimately benefit from the federally supported SBIR technologies. For real victory, not only will the individuals and companies be learning about regulation, reimbursement, trials, partners, and IP in ways they never have before, but the government will also be learning about how to continue to create a bridge with the private sector that will lead to novel technologies and to prevent the challenges and burdens that stifle innovation.

There is hope. While Mr. Blank’s model is only one way for potential startup success, other agencies such as DOE have launched its own $2.3 million “Lab-Corps,” commercializing clean energy technologies using the same lessons as NIH. Moreover, Blank is in talks with NYU and Johns Hopkins in addition to UCSF,Georgia Tech and University of Michigan medical and bioengineering departments about adding the Lean LaunchPad methodology.

Perhaps, the greatest outcome of the I-Corps and Lab-Corps cohorts will be the lessons they share with the federal government about IP, scaling and regulation. That is the kind of “change the world” approach Mr. Blank and I-Corps hope to create.

Syllabus for the class can be found here.

All of the team videos and presentations can be found here.

Twitter feed for the course and events can be found here.