I first remember hearing about sickle cell anemia as a teenager. I knew the disease affected mostly African Americans and I knew there was no cure.

I first remember hearing about sickle cell anemia as a teenager. I knew the disease affected mostly African Americans and I knew there was no cure.

I first remember hearing about sickle cell anemia as a teenager. I knew the disease affected mostly African Americans and I knew there was no cure. I remember a high school classmate whose mother was afflicted with the disease and that she was, more often than not, in bed in a weak and debilitated state and in and out of the hospital for blood transfusions. I saw how this impacted my friend and her family. Mrs. Trice was the only person I can ever remember meeting with sickle cell anemia, but it wasn’t until I began working in this industry three years ago that I learned it was classified as a rare disease.

I first remember hearing about sickle cell anemia as a teenager. I knew the disease affected mostly African Americans and I knew there was no cure. I remember a high school classmate whose mother was afflicted with the disease and that she was, more often than not, in bed in a weak and debilitated state and in and out of the hospital for blood transfusions. I saw how this impacted my friend and her family. Mrs. Trice was the only person I can ever remember meeting with sickle cell anemia, but it wasn’t until I began working in this industry three years ago that I learned it was classified as a rare disease.

In the U.S., a disease is considered rare if it is believed to affect fewer than 200,000 Americans. Certain diseases with 200,000 or more affected individuals may be included in this list if certain subpopulations of people who have the disease are equal to the prevalence standard for rare diseases, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

What is sickle cell disease and who is affected?

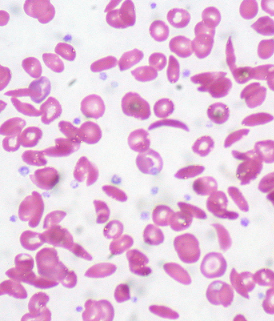

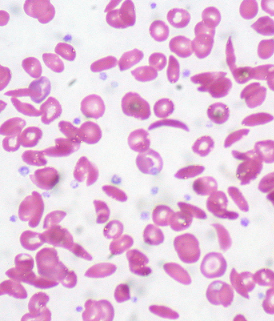

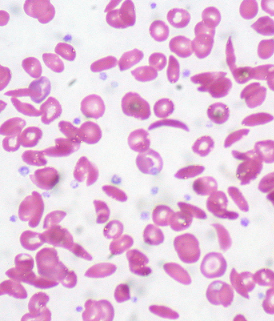

Sickle cell disease is a defect of the hemoglobin that affects the shape and flexibility of the red blood cells. The abnormal hemoglobin in a red blood cell of an afflicted individual is rigid and crescent or sickle shaped instead of flexible and round like that of a normal red blood cell. These defects cause the cells to get stuck in small blood vessels, thereby blocking their delivery of oxygen to organs like the lungs, kidneys and liver, as well as joints and tissues. Patients with this hereditary disease experience its major symptom: debilitating pain. This requires heavy doses of narcotic pain killers. Blood transfusions can also provide relief, but just temporarily. Beyond excruciating pain, this condition can also cause irreversible organ damage.

People of African, Mediterranean basin, Saudi Arabian, Latin American and Asian origin are impacted by this disease. One in 500 African Americans is impacted and one in 12 African Americans carries the sickle cell trait, according to University of Illinois College of Medicine at Chicago.

NIH study grabs attention of University of Illinois hematologist

When an NIH study reported they could do stem cell transplants in sickle cell patients without using chemotherapy and still receive good results, Dr. Damiano Rondelli, University of Illinois Hospital hematologist, took notice. (In the past, the chemotherapy requirement has been a standard practice meant to kill off a patient’s own cells and prep the body to accept new ones, but this was a barrier to some patients because organ damage left them in a weakened state already. Chemotherapy would prove too risky in these individuals.) Dr. Rondelli and his colleagues took action. “The results were amazing,” he states. “Because of our large patient population of sickle cell, we opened the trial here.”

Promising trial results

Dr. Rondelli and team have seen promising results in their trial thus far. In the case of a Chicago area family where one brother was the donor for two of his siblings, Dr. Rondelli states that the post-transplant blood tests reveal the sickle cell is gone and the red blood cells are completely from the donor (i.e., normal). The video below from WGN tells the story in the family’s own words.

Image courtesy of Ed Uthman on Flickr (CC BY).