Since my presentation at the 2013 Connected Health Symposium, “Making Health Addictive,” I’ve been posting on this topic in order to explain some of the concepts in more detail and to get your collective feedback (always incredibly helpful). Previous posts include a framing post, and further detail on what I proposed as three strategies to achieve addiction to healthy behaviors, “Since my presentation at the 2013 Connected Health Symposium, “Making Health Addictive,” I’ve been posting on this topic in order to explain some of the concepts in more detail and to get your collective feedback (always incredibly helpful). Previous posts include a framing post, and further detail on what I proposed as three strategies to achieve addiction to healthy behaviors, “Make it About Life,” “Make it Personal” and “Reinforce Social Connections.”

In early February, I wrote about tactic one, Employ Subliminal Messaging. Here is my post on the second of three tactics, Use Unpredictable Rewards. The third and final tactic, Use the Sentinel Effect, will follow in my next post.

Making health addictive is really about harnessing the power of our fascination with mobile devices, particularly smartphones. We check these devices up to 150 times per day. What if we put a personalized, relevant, motivational and unobtrusive message in front of you some of those times? Could we induce permanent behavior change? I am searching for examples of these customized mobile, personalized messages and any resulting behavior change, so if you know of any, please let me know.

The concept of unpredictable rewards brings us closer still to the vision of what Making Health Addictive might look like on your mobile device. This tactic is what the mobile industry has capitalized on to get you to check your device 150 times a day. Now, we just need to corral the power mobile devices yield, to call your attention to relevant, personalized health messages, and change our behavior for the better.

This tool for behavior change is not new. In 1948, when B.F. Skinner did his famous operant conditioning experiments, he measured rat salivation in response to presenting a food pellet to the rat. In the background, he also rang a bell when the food pellet was presented. After a while, he observed that the rat would salivate when the bell rang, whether the food pellet dropped or not. The response was even stronger, however, when the food pellet was presented randomly. This observation was the beginning of the science of variable rewards.

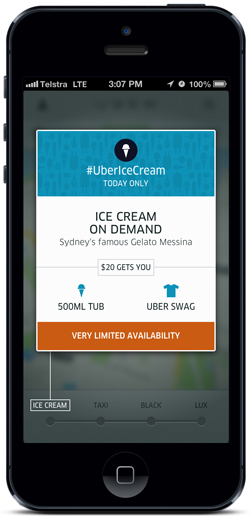

Advertisers use this concept often, as they know how effective it is. One recent noteworthy example comes from the company Uber. Undoubtedly you have heard of Uber. They’ve turned the process of flagging a taxi upside down and in the process created a much more pleasant customer experience. Recently, they have done something else to increase the likelihood that a user will open their app. Every now and then, when you open the Uber app, you will see an offer for something completely unrelated to getting a ride. It might be a discount on flowers or show tickets. They do this randomly and even though it’s not part of their core business, they have demonstrated that people open the app more often knowing that this unpredictable reward might be there.

Actually, when you think about it, this is the fundamental psychology that underlies why we check our mobile devices so many times. There is so much new content (emails, texts, news, etc.) and it changes so rapidly that we become like Skinner’s rats. We have to check the devices constantly.

This tactic marries quite effectively with subliminal messaging. If we could design an app so that every time you check your phone, there is a relevant health message in the path (it can’t appear every time and it can’t be obtrusive; it might not need to even be noticeable), we may be able to change health behavior in a way that would seem almost effortless.

Recall our study on the use of text messages to improve sunscreen adherence. In this study, we sent folks in the intervention arm a daily text message with the weather report and a reminder to put on sunscreen. The group did remarkably better than a group of subjects who did not receive the messages. When we asked the subjects what they found compelling about the text messages, many said they liked getting the weather report. They barely paid attention to the messaging on sunscreen use. But it changed their behavior.

There is something to this. Last fall, Facebook released an app that would take over your home screen so that any time you open your phone, you see your Facebook updates before anything else. It hasn’t done too well, perhaps because it feels too invasive. But what if your health plan (or provider in an accountable care world) offered you a reduced premium for services if you agreed to get a health message mixed in (randomly but on average every 10 emails or texts) with your other messages.

Would people consider this too invasive? Would the reduction in premium costs be enough to motivate use?

What are some other applications for unpredictable rewards to improve health?