When we think of nurses, we imagine women in white, their thick-soled shoes beating a fast path toward needy patients. Or we remember pictures in children’s books of Florence Nightingale’s elegant form passing through barracks of wounded soldiers; the only light in the room comes from the single lantern she carries. These traditional images of the nurse aren’t complete without one essential item: her cap.

When we think of nurses, we imagine women in white, their thick-soled shoes beating a fast path toward needy patients. Or we remember pictures in children’s books of Florence Nightingale’s elegant form passing through barracks of wounded soldiers; the only light in the room comes from the single lantern she carries. These traditional images of the nurse aren’t complete without one essential item: her cap.

Nurses’ caps had both practical purposes and symbolic significance. Though it’s difficult to pin down an exact time period when wearing caps became standard practice, there is a mild consensus that they became prevalent in the mid-1800s. Some say that caps were originally donned by the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul in Paris, where one of the first official nursing schools was established in 1864.

Since nuns were among the first women to be trained as nurses, and to train nurses in turn, the original caps were akin to habits. Social mores of the time also necessitated the caps, since women were expected to keep their heads covered – even indoors. These longer caps served more than just the dictates of fashion; they also helped to keep a nurse’s hair out of her face as she worked, which facilitated more sanitary conditions.

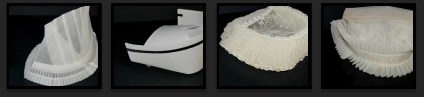

Below see images of our very own employee nurses caps:

These nurses caps were collected from LifeBridge Health employees.

For Florence Nightingale, unarguably one of the leading lights in nursing, the cap was inextricable from the profession itself. When she organized a mission of mercy to Scutari during the Crimean War, Nightingale required her nurses to wear a special uniform and nurse’s cap. After the war, she set up the Nightingale Training School at St. Thomas’ Hospital; there, the longer, more bonnet-like caps were eschewed, and students wore shorter, square-shaped caps with their uniforms.

In many ways, the history of the nursing cap correlates to the history of women’s social liberties. As time passed and long hair was no longer de rigueur, the caps served as signifiers for a particular nurse’s educational background and level of expertise. Different nursing programs and hospitals offered their own caps: some caps were ruffled and frilled, others were starched stiff and box-like; some were Dutch-styled, winged caps, others looked like knotted kerchiefs. For instance, if you were a patient in the 1900s, and the woman checking your pulse was wearing a cap delicately fluted with point d’esprit lace, you knew that you were in the capable hands of a graduate from the University of Maryland School of Nursing. This cap was called “the Flossie” in honor of Florence Nightingale.

Though caps like “the Flossie,” or Philadelphia General Hospital’s “double frill,” or the Bellevue Training School for Nurse’s simply — yet aptly — named “fluff” were beautiful to behold, they were cumbersome to care for. Some caps had to be continually replaced, at expense to the nurse herself. Still, the unique beauty of these caps, and the immaculate orderliness they evoked, no doubt inspired generations of future nurses.

Caps also facilitated a sense of community among nurses, no matter where they ended up practicing. In a letter to the American Journal of Nursing, dated 1931, a nurse named Julia Gardner wrote, “When entering a strange hospital, as an affiliating student or visitor, it is almost like seeing a familiar face to see the cap of one’s own school on a nurse there.”

Caps were bestowed to both student and graduate nurses in a rite of passage known as a capping ceremony. Early ceremonies were conducted after three, six, nine or 12 months of training (whatever constituted a probationary period for each school). Sometimes these “probationer’s caps” were plain white versions of the graduate’s cap – in which case, completion of the nurse’s training was marked by the addition of a black stripe. Other schools opted to make their student and graduate caps entirely different. Capping ceremonies were often held in churches, where, before the students’ friends and families, they’d be “capped” by an instructor or by a mentor student, usually referred to as a “big sister.”

Being capped symbolized accruing the knowledge and prowess needed to truly serve as a nurse. Capping ceremonies were often emotional affairs with guest speakers testifying to the value of nurses within their communities. As one speaker at a 1938 graduation powerfully expressed, “the nurse’s cap means to you what the soldier’s uniform means to him. When this cap is pinned on your head, it means you have become a member of one of the noblest professions and have subscribed to its ideals of service. You are no longer merely an individual responsible for her own acts; you are part of the nursing profession.”

But as women in general become more enfranchised and empowered in the workplace, the nursing profession expanded into administrative areas and caps began to feel like relics of a bygone era. The 1970s and 80s also saw an influx of men into the field, which forced a change in tradition. Caps were gradually swapped out for the more gender-neutral, easily maintained, and (some might say) elegant pins. And caps, once thought of as the epitome of sanitary care, were now seen as harbingers for bacteria and other harmful contaminants.

Though you’re far more likely to find a nurse’s cap in a glass case commemorating a hospital’s rich history before you’ll find it on a ward, for many nurses, it is still a powerful reminder of the hard work performed and the obstacles overcome to find a foothold in their chosen profession. Nurses must often be all things to all patients, yet the breadth and depth of their work is, at times, all-too-easily overlooked. These nurses find their thoughts best expressed by Bonnie Miller, an RN at the Sandra and Malcolm Berman Brain & Spine Institute: “I may never wear [my cap], but I earned it.”

-Laura Bogart