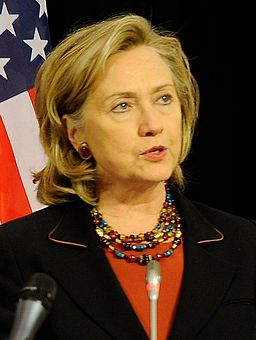

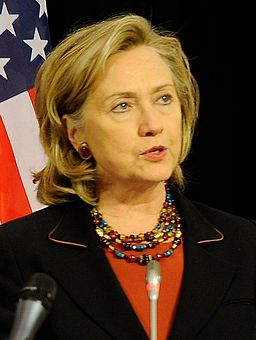

In the waning days of 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton sparked a wildfire of a news cycle when an MRI scan picked up a cerebral venous thrombosis (or, in other words, a blood clot in the vein running between her brain and the spot of skull behind her right ear). This hospitalization came just three weeks after Clinton suffered a concussion, and a myriad of breathless headlines turned the concussion and the blood clot into a cause and effect.

However, Kevin Crutchfield, M.D., director of the Comprehensive Sports Concussion Program at the Sandra and Malcolm Berman Brain & Spine Institute at LifeBridge Health (who was not involved in Clinton’s treatment), cautions us against making immediate assumptions. “Hillary Clinton’s blood clot might not be caused by her concussion,” he explains. “She may have an underlying hypercoagulable syndrome, which could have some genetic causes.”

Back in 1997, crippling pain in her right foot sent her to Bethesda Naval Hospital, where doctors found a large blood clot behind her right knee. Ten years later, in an interview with the New York Daily News, Clinton referred to this as “the most significant health scare I’ve ever had.” She went on to add, “You have to treat it immediately – you don’t want to take the risk that it will break loose and travel to your brain, or your heart or your lungs.”

This subsequent blood clot was discovered during an MRI ordered as part of the follow-up exam for Clinton’s concussion. CT or MRI scans aren’t always part and parcel of treatment for a concussion: They’re generally recommended when someone loses consciousness as Clinton did (though not all concussions involve loss of consciousness); when their speech and language skills show signs of deterioration; when they exhibit a loss of coordination and fine motor control; or when they experience vision changes (such as reduced or lost vision, or even double vision). So the blood clot may very well have been an incidental find.

As the most-traveled secretary of state in recent memory, Clinton racked up the frequent flyer miles; she also picked up a nasty stomach virus that left her fatigued and dehydrated, which, in turn, caused her to faint and hit her head. Crutchfield also points out that dehydration can also “predispose susceptible individuals” to blood clots. Dehydration thickens the blood and slows its flow, which can cause clotting.

Clinton’s plight reminds us that concussions don’t just happen to star athletes and weekend warriors. “The most common cause of concussions is falling,” says Crutchfield. If you happen to be with someone when they take a tumble and bump their head, be on the lookout for signs that they’re becoming physically weaker or sleepy. If unconscious check their pupils. If one pupil is significantly larger than the other, immediate transfer to trauma hospital is needed. If the person becomes agitated or confused, complains of a searing headache, starts seizing or vomiting, or experiences paralysis on one side of their face, they’ll need immediate medical attention.

Recovery time varies for each individual, and can be dependent upon whether they have any underlying conditions. “There’s no cookbook for healing from a concussion,” Crutchfield adds. Since there’s no perfect cocktail of ingredients that can undo a concussion, proper intervention – such a seeking the care of a physician specifically trained in brain injuries – is vital.