When speaking about Belgium, Dr. Florence Hut, physician-in-chief at CHU Brugmann (Brugmann University Hospital) is full of pride. Only a few days ago, Francois Englert, a Belgian theoretical physicist won this year’s Nobel Prize for Physics, bringing the total number of the country’s Nobel Prize laureates to 11. But to Dr. Hut, what made her even prouder during her lecture at my health care policy class at Columbia University is Belgium’s almost-too-good-to-be-true health care system.

The country’s infant mortality rate is 3.3/1,000 newborns, almost 50 percent lower than the number in the U.S.; 99 percent of Belgian people are insured compared with 84 percent of American; the obesity rate is 14 percent in Belgium and 36 percent in the U.S.; the total expenditures on health per capital in Belgium is only half compared to the U.S…. But one thing that really differentiates the Belgian health care system from the U.S. is more than 90 percent of Belgians are satisfied with it.

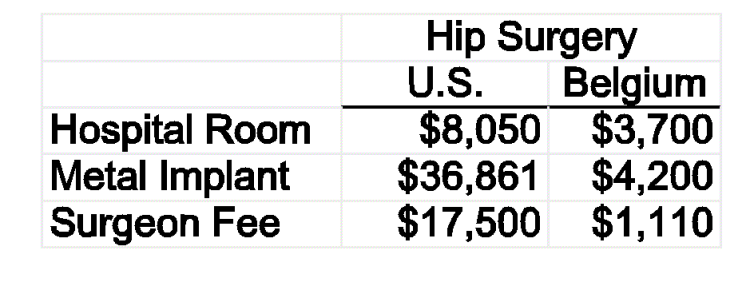

Source: 2012 Comparative Price Report by the International Federation of Health Plans. Photo Credit: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/02/health/colonoscopies-explain-why-us-leads-the-world-in-health-expenditures.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

The timing of the lecture was particularly opportune—when dealing with a government shutdown, a heated ongoing debate over universal coverage, an expensive and increasingly dysfunctional health care system and growing concerns with the future of the world’s largest economy and leader of the free world, hearing a health care success story cannot be more refreshing and inspiring.

Belgium’s success, according to Dr. Hut largely relies on the trust between citizens and the government—people genuinely believe its government, the single payor of their health care makes smart decisions and works in the best interest of citizens. The trust is fostered by a strong sense of solidarity—it is every citizen’s responsibility to contribute to health care, a basic human right, when they are healthy. The Belgian mindset is probably shocking to many people living here in the United States, where government has been long regarded by many as an enemy of freedom and a culture of volunteerism and individualism has been deeply rooted in almost everywhere of the society. Ironically, “personal responsibility” makes Belgian health care system sustainable and “volunteerism” makes the U.S. system so fragmented and leaves millions of people out of coverage.

Comparison of the cost for a hip surgery in U.S. and Belgium (Source/photo credit: http://qualityhealthcareplease.files.wordpress.com/2013/08/hip-costs-us-belgium-2.png)

From policy makers, economists to scholars, many have offered remedies to fix health care in the U.S. but meaningful and tangible improvements have been limited. The world’s most expensive health care system does not generate the best results. If the Belgian health care system is any indication, the answer to fixing the U.S. health care system may not be tactics but a new perception of health care that is built upon mutual trust and humanity. Because when trust and humanity are gone, we see serious issues that negatively affect everyone in the system: defensive medicine, low efficiency, poor outcome, alarming safety records and most of all, the indifference for those who rely on safety net for care in a country where so many strongly believe “personal responsibility” and free market are panaceas.

What Dr. Hut could not comprehend was why so many people in this country have been trying so hard to stop a law that only brings incremental benefits for those who need them the most. Call the Belgian system “socialized medicine,” but the results speak for themselves. As the only major country in the Western world that doesn’t have universal health care coverage and the one with the highest health care spending per capita, the U.S. experience has clearly demonstrated why health care cannot function well without strong involvement of government.

The struggle of the Affordable Care Act is the struggle for the future of this country. If the trust and humanity can be rebuilt through the struggling, all the debates and negations might be all worth it.