I’m going to summarize in a single paragraph a debate that has been raging in health policy for the past two decades.

On one side is what I call the health policy orthodoxy. On my side is a small group of people that believe markets can work.

I’m going to summarize in a single paragraph a debate that has been raging in health policy for the past two decades.

On one side is what I call the health policy orthodoxy. On my side is a small group of people that believe markets can work.

The debate goes like this. Them: The marketplace can’t work in health care. Patients don’t have enough knowledge; there is unequal bargaining power; and medicine is a profession, not a business. Us: What about cosmetic surgery? Them: That’s an exception. Us: What about Lasik surgery? Them: That’s another exception. Us: What about medical tourism? Them: That’s only for rich people. Us: What about Health Savings Accounts? Them: That’s only for healthy people. Us: What about walk-in clinics? Them: Okay, maybe the market can work for small stuff, like flu shots, but it can’t work for expensive procedures, like joint replacements and heart surgery.

Do you know how many man hours have been spent repeating these sentences at conferences, briefings and hearings and in editorials and journal articles? Don’t ask.

On the last point (about expensive procedures), I think the other side has had the better argument. Until now.

In my book Priceless I made a bold claim. I predicted that most employers could cut the cost of hospital care in half by an aggressive version of “value-based purchasing,” also called “reference pricing.” I also predicted (again, without any evidence) that if a significant number of patients were involved, the hospital market would begin to resemble a competitive market.

Here’s how it works. Employers pick out a few low-cost, high-quality facilities and agree to pay all or most of the cost of the procedures at these facilities. Employees are free to patronize other providers, but they have to pay the full amount of any extra expense.

A recent example is Wal-Mart, which has selected seven centers of excellence for elective surgery. Employees can go to other providers, but they may face out-of-pocket charges of $5,000 or $6,000. Lowe’s has a similar arrangement with the Cleveland clinic for cardiac surgery. This is what we call “domestic medical tourism” at the NCPA. I like it. But it’s not the only approach.

Safeway, the national grocery store chain, has established a reference price for 451 laboratory tests ― set at about the 60th percentile (60 percent of the facilities charge this price or less). If the employees choose a more expensive facility, they must pay the extra cost out of their own pocket.

Lab tests are relatively inexpensive, however. How well would reference pricing work for big ticket items? WellPoint, operating in California as Anthem Blue Cross, started with joint replacements and the results are fascinating. They are planning to extend the approach to as many as 900 additional procedures, beginning next year.

Like other third-party payers, WellPoint discovered that the charges for hip and knee replacements in California were all over the map, ranging from $15,000 to $110,000. Yet there were 46 hospitals that routinely averaged $30,000 or less. So WellPoint entered an agreement with CalPERS (the health plan for California state employees, retirees and their families) to pay for these procedures in a different way.

WellPoint created a network (I am informed that this is not technically a “network” but I’m going to call it that anyway) consisting of the 46 facilities. There was no special negotiation with these hospitals, however. WellPoint simply encouraged their enrollees to go to there. Patients were free to go to elsewhere, but they were told in advance that WellPoint would pay no more than $30,000 for a joint replacement outside the network. (At all the hospitals, patients pay a 20% copayment up to $3,000.)

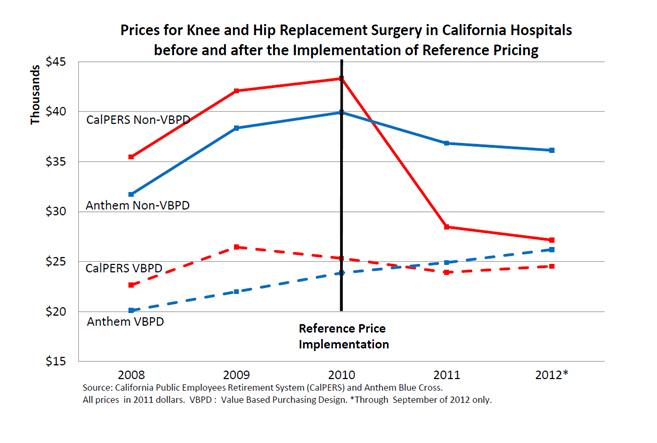

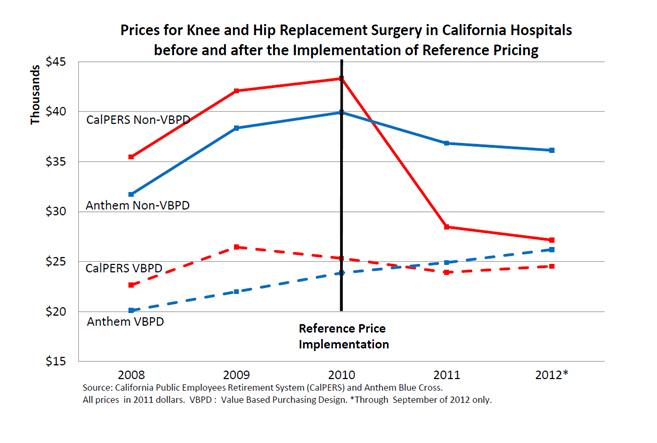

Take a look at the graph below. The patients in this graph have been adjusted for case severity and geographical diversity in a study by Berkeley health economist James Robinson and his colleague Timothy Brown. The bottom two lines show patients who went to the 46 hospitals. The red line reflects the average cost for CalPERS patients who, beginning in 2010, were enrolled in WellPoint’s new program. The blue line is the control group. As the figure shows, there is not that much difference between the two populations in terms of the cost of their procedures.

Now look at the top two lines. The red line represents the average cost for CalPERS patients who went outside the network (about 30% of the total). Beginning in 2010, they undoubtedly told the providers they had only $30,000 to spend. As the figure shows, the cost of care at these hospitals was cut by one-third in the first year and continued heading toward the average “network” price over the next two years.

This is dramatic evidence that when patients are responsible for the marginal cost of their care (and therefore, providers have to compete on price) health care markets become competitive very quickly. Remember, the insurer is not bargaining with these out-of-network providers. The patients are.

Look at the uppermost blue line. These are (control group) patients who are not telling providers they have only $30,000 to spend. Nonetheless, their price/cost of care begins declining in 2010 as well. This is exactly what would happen in the market for canned corn or for loaves of bread. People who comparison shop affect the price paid by those who don’t.

Now ask yourself this very important question: Who is more powerful at controlling health care costs? Huge third-party bureaucracies negotiating with providers? Or patients paying the marginal cost of their care?

Game. Set. Match.

Postscripts

- There is a public policy issue here. Wherever I look, I find there are people in the private sector who are light years ahead of the government. Not everybody in the private sector, of course. But there is certainly no reason for the government to be spending millions of dollars on pilot programs and demonstration projects. The interesting innovations are already being done privately. Almost everything the government is doing is pointless waste.

- Uwe Reinhardt had a post on reference pricing the other day. However, in his telling of the story, the focal point is the third-party payer, who is seen as the main actor ― pushing (nudging?) patients to make lower cost choices. This is a very common point of view, but it misses what is most important. In California, the third-party payer set the market in motion, but then became less and less important through time. Actual prices were then determined by the interaction of thousands of individual patients and providers.

- Whereas reference pricing is often portrayed as a burden for patients, done correctly it liberates them. This would be ever so much clearer if all the patients had a generously funded Health Saving Account.

- WellPoint’s own analysis shows that the quality of care at the 46 hospitals is as good as or better than in out-of-network hospitals. But in the future that might change. We know that when providers compete on price they also tend to compete on quality. And it is here that the HSA is really important. Providers are more likely to compete on quality if patients have the funds on hand to pay more if higher quality costs more.

Finally, I hope no one will conclude that these developments are the result of the Affordable Care Act. If anything, the ACA is actually an obstacle to sensible reform. Some health plans have been reluctant to try out reference pricing for fear the Obama administration will find it in violation of the out-of-pocket restrictions imposed by ObamaCare. (See this discussion by Jamie Robinson and Kimberly MacPherson.)