The UN estimated that in 2012 for every 100,000 live births in the country, 510 women die from pregnancy, with significant disparities between the death rates of Black slaves and Arab owners. Of even greater concern is that due to female slaves being forced to have children with owners, an estimated 71.3 births per 1,000 live births are to adolescents who suffer extreme mental and physical abuse. In John Sutter’s captivating CNN coverage of oppression, Slavery’s Last Stronghold, he reports that, “In Mauritania, the shackles of slavery are mental as well as physical.” He goes on to describe the political and societal methods through which the lighter-skinned Arabs maintain their ownership of the dark-skinned peoples.

Kevin Bales, an expert on modern day slavery, wrote in his book Disposable People that even if someone of bondage attempts to leave an owner, “for most, freedom means starvation.” He claims that because slaves are, “immediately recognizable by color, clothing and speech” they will not be given shelter or proper care by others. Further, Mr. Bales asserts that on the streets of Mauritania, “ there are already a good number of beggars, many of them disabled, to remind slaves of where they almost certainly end up” if they were to leave their masters.

“Mauritania is a country with scarce resources – including access to medical care. The health needs of slave owners come first in Mauritania; the health needs of slaves come last. Slave children are chronically malnourished. Slave women are frequently victims of sexual assault by their owners and the devastating health problems that result.” says Sean Tenner, Co-Founder of the Abolition Institute, an organization focused on ending Mauritanian slavery and a veteran of numerous public health campaigns.

Despite the country’s open system of ownership, to date, the US has not taken a stance against the practice. The country, located on the western fringe of the Sahara, is not densely populated, and therefore practices of the owners are not easily monitored by the government. Further, the country’s ruling elite makes no attempt to fight slavery, as they claim to the UN that slavery does not exist.

However, what is most surprising in 2013 is not the lack of Mauritanian action against their own traditions, but the lack of American recognition and action. At a time when the US tries to face its own challenges with inequality, health, human rights and foreign policy, it is saddening to know we also neglect others.

Mauritania is also deeply divided by access to basic human rights such as health. In 2000, it was estimated that only 37% of the country had access to safe drinking water and 33% to adequate sanitation. Life expectancy has hovered around 57 for both sexes for many years, but with great disparities between the slaves and owners.

The US has done nothing to date but overlook the unlivable health conditions and human rights violations in the region for those that are born into bondage.

In the United States however, one group is taking action to make Americans aware of the atrocities faced by the Mauritanian slaves, and the health and human rights violations that exist. The Abolition Institute, founded in Chicago by Mr. Tenner and former Mauritanian slaves, was recently formed to end the practice of slavery in Mauritania, and bring freedom to those suffering under the inhumane circumstances of maltreatment, malnourishment and abuse.

The organization does everything from educating the public on the religious aspects of modern day slavery to informing about the living conditions and health of slaves through noting disparate practices such as “gavaging” in Mauritania, where women of Arab decent try to gain weight to show that they are wealthy elite and not poor slaves with emaciated frames.

However, the devastating effects of slavery run much deeper than the physical effects. The extreme consequences the effects of slavery have on mental health know no bounds.

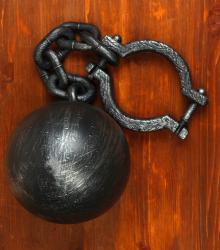

In Slavery’s Last Stronghold, a leader of an abolition group tells Sutter that many similarities exist between modern slavery in Mauritania and that in the United States before the Civil War, but that the one fundamental difference between the two in his mind is the use of physical restraint. “Chains are for the slave who has just become a slave, who has . . . just been brought across the Atlantic,” Boubacar said. “But the multigeneration slave, the slave descending from many generations, he is a slave even in his own head. And he is totally submissive. He is ready to sacrifice himself, even, for his master. And, unfortunately, it’s this type of slavery that we have today” — the slavery “American plantation owners dreamed of.”

(Slavery / shutterstock)