This post appeared originally in MedPage Today, where I wrote it as part of our pricing transparency partnership with MedPage Today. Re-posted with permission.

Summary: “I live in metro NY and received a bill for $2200 (approx) for a mammo/Ultrasound, of which approximately $767 was covered by insurance. I was balance billed $1,712,” the email said. “I am a 42 y.o. female physician with a family history of ovarian cancer, and I am covered by Blue Cross/Blue Shield. I was frankly horrified by the costs.” Of course we were interested: our research shows that a mammogram price can range from free (preventive, under the Affordable Care Act) up to $2,786.95. So … how much does a mammogram cost? Click for more details, or …

The email came from Kimberly Greene-Liebowitz, MD, MPH, who works at CityMD, the New York area urgent care chain. A practicing doctor, and possessor of a master’s degree in public health, she found us when researching costs, and reached out with a sense of deep outrage.

Her provider was Phelps Memorial Hospital in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y., and the insurance company is Anthem Blue Cross via her husband’s employer.

We know mammogram costs can vary widely, though we have learned that cash rates for a regular screening mammogram (without ultrasound) in the New York area can range from around $50 to $1,126, according to our survey of providers and contributions from community members. When we did our crowdsourcing partnership with WNYC public radio in New York about the price of mammograms, we learned that prices and payments vary widely, but we commonly heard that women were getting a mammogram and an ultrasound for somewhere around $800. We wrote about that here and here.

What was prescribed and why, I asked? It was a diagnostic mammogram, not preventive, so not automatically covered under the Affordable Care Act?

She answered by email: “I do not have the prescription, unfortunately. I believe the ordering was for bilateral mammogram and ultrasound for ‘pain.’ As a child I had a hemangioma on my right breast that gradually involuted and disappeared over time. I now have dimpling on the lower medial aspect of my right breast which I believe is related to this involution and the decreased elasticity of my breast tissue, but given the concerns about breast cancer I pursued this.”

“Last July my gyn ordered a unilateral mammo/US to assess this and I followed up with a breast surgeon. At the time there were no findings. This March the study was repeated (I’m supposed to be doing this every 6 months, but I fell off the wagon a bit) only bilateral since it was time to do the other side anyway. That study was also read as negative. I believe this was billed as ‘diagnostic’ because of the ‘pain’ code. Although there has never been any pain — only the dimpling, and that doesn’t exist as a code choice in the billing system. The left breast was a typical screening mammo & ultrasound. I have dense breasts so the ultrasound is indicated.”

She said it never occurred to her to discuss price, because they were insured, and the previous summer’s mammogram had cost about $1,300. This time, she called Phelps after getting the bill: “The first woman I spoke to was lovely, and told me she would submit the bill for review. She told me she could not reduce it without authority. Several weeks later they called me back and told me we would have to pay the bill in full.”

After that, she wrote, “I contacted the head of billing, the patient services rep, DFS [the New York State Department of Financial Services], our Senators & Representatives, and our state legislators — Andrea Stewart-Cousins and Amy Paulin. None have responded. Though DFS was very nice on the phone. My conversations with Phelps largely centered on the people with whom I spoke defending their billing practices and asking me in a condescending tone if I understood my bill yet.”

She and her husband pay annual premiums of $2,408.90, and their policy has an annual deductible of $5,700 and annual out-of-pocket maximum of $9,500.

What else you might need to know

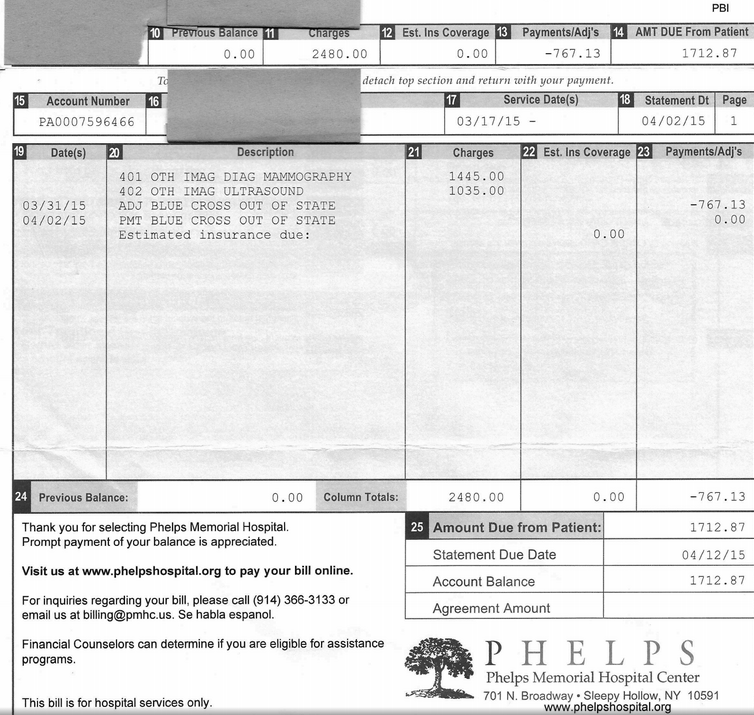

The bill from Phelps was for $2,480, but the EOB has total charges as $2,718.82, confusingly. Both helpfully have the same thing for “your responsibility,” that $1,712.87.

The hospital bill listed $767.13 as “ADJ BLUE CROSS OUT OF STATE,” meaning, we surmise, the negotiated rate between hospital and provider is $1,712.87. The EOB says “amount allowed by your benefit” is $1,712.87.

I asked her about the discrepancy, and she answered: “I have no idea why there is a discrepancy between the ‘charges’ on my Phelps bill ($2,480) and the ‘total charge’ on my EOB ($2,718.82). It definitely wasn’t for physician fees because we received a separate bill for the physician fees AFTER we finally paid the Phelps bill.”

Phelps recently joined the North Shore-Long Island Jewish hospital system, after a number of years as a member of the Stellaris network in Westchester County.

What the hospital said

With Greene-Liebowitz’s permission, I called the hospital, sending them her email granting permission to discuss this issue. I asked Maria Malacarne in patient accounts to review the bill, and asked if that was not a fairly expensive mammogram and ultrasound. She said, “This was applied to her deductible. The prices are fairly comparable to hospitals in the area.”

I asked how the actual bill was figured, and if she could explain the $2,480-$2,718.82 difference.

She said the HCRA surcharge of 9.63% applied. What is the HCRA surcharge? “It’s a tax. On the bill it just says ‘surcharge 9.63%.’ Every hospital in New York has that surcharge.” (This 9.63% is the difference between the billed $2,480 and the charge of $2,718.82. Explaining HCRA? She couldn’t. Gahhh. I’ll follow up on this.)

How was the patient responsibility figured? She said, “We were expecting $1,562.40. That was the reimbursement that we expected from Blue Cross. That was adjusted up $150.47….They chose to put more than that toward the deductible. We billed exactly what Blue Cross told us to bill.”

I asked her what the Phelps rate would be for those procedures for a self-pay patient, paying cash, and she said, “We have private-pay rate. For outpatient services it’s about 50% of charges.”

So could Greene-Liebowitz have asked for that rate? No, Malacarne said: “If she’s fully insured, she can’t come in and say ‘I’m fully insured but I am not going to use my insurance.’”

What the insurance company said

Next stop: the insurance company. After Greene-Liebowitz filled out a HIPAA privacy waiver, I talked with Dr. Scott Breidbart, chief medical officer of Empire BlueCross Blue Shield, by phone. I asked him about the charges.

For a diagnostic bilateral mammogram, CPT code 77056, “we allowed $866,” he said. (Medicare pays $132, according to the Medicare Physician Fee Finder.) The second procedure, an ultrasound, CPT 76641, is $715 (Medicare pays $130.83); the third, a computer-aided diagnostic charge, CPT 77051, for this year is $132 (Medicare pays $11.23).

Did that seem expensive? I asked. “It depends tremendously on whether it’s done in a hospital or at a freestanding radiologist,” he said. “Had it been done at a radiologists’ office, it would be a lot less.”

Had Greene-Liebowitz called, Breidbart said, the insurer would have told her to go to a less expensive place — probably a radiologist’s office.

But how is she to know that? I asked. Is it fair to expect her to call? And isn’t it true that both hospital and insurance company are notoriously bad at phone service for insured people, and generally at explaining costs?

“You’re absolutely right that it is expensive, and it’s not easy for people to find out how much health care costs,” he said. “But it is do-able.”

“When you say it’s unfair and that it’s difficult, you’re right. I can’t disagree with anything that you’re saying. You’re also right that people do take responsibility when it is their own money.”

“It does upset people when the money comes out of their pocket,” he said.

“It’s a shift in how health care is delivered, and while that shift is taking place, people are spending more money than they expected to, and that they wanted to,” he added. “I feel for her. You’re right, it’s tough.”

I mentioned the Phelps cash rate, and he objected: “If she were to offer cash, she would pay the hospital’s billed rate, which is far higher,” he said. After I explained the cash rate, he said:

“If the hospital is offering to do these tests for less than they’re charging us, we would certainly want to know about it.”

(Note: Insurance companies and providers commonly negotiate reimbursement rates behind closed doors, and cash or self-pay rates are common. See this paper and several blog posts, here and here, for details.)

The rest of the story

Greene-Liebowitz ultimately paid the bill, she said, because of the fear of an unpaid bill compromising her credit score.

The fact that she’s extremely well educated and conversant with the health care system does not mean that she’s protected from extraordinary costs. It does make this a paradox of sorts: if Greene-Liebowitz is at risk, what about others?

There are also reasons for perceiving the health care marketplace in new and interesting ways. I heard the other day from Dr. David Belk, a California physician who has made something of a study of billing. He is, not surprisingly, not a fan of insurance companies (most doctors share his opinions).

He emailed a link the other day to a video he had done recently about why “insurance companies want hospitals and other health care workers to over-bill by so much.” Here’s the video. His belief: Insurers like blog posts such as this one because they frighten people into buying insurance.

Finally, we are often asked if people shop around for health care. During our reporting on this story, Greene-Liebowitz wrote: “Interestingly, this experience has changed my health-care purchasing behavior: I was supposed to get an X-ray and though I was unable to get anyone in the hospital to tell me how much it would cost if I billed the X-ray through insurance, I found the out of pocket charge to be unreasonably high (this was at Columbia) and I opted to look for an outpatient radiology center instead; and when I had bloodwork done recently, I decided to pay out of pocket rather than submitting the charges through my insurer.”

Jeanne Pinder is founder and CEO of ClearHealthCosts.com, a New York City startup bringing transparency to the healthcare marketplace. Check out the alliance formed between MedPage Today and ClearHealthCosts to tackle price transparency with tools for healthcare providers to join in the effort, and read more in a letter from MedPage TodayEditor-in-Chief Peggy Peck.