Jimmy Carter once said that America is not a melting pot, but a beautiful mosaic. We have all sorts of people here, but we want them to maintain their unique identities, not assimilate into some generic unity. However, this very characteristic that makes our nation so wonderful also provides the context for stigma, segregation, and hate crimes.

Jimmy Carter once said that America is not a melting pot, but a beautiful mosaic. We have all sorts of people here, but we want them to maintain their unique identities, not assimilate into some generic unity. However, this very characteristic that makes our nation so wonderful also provides the context for stigma, segregation, and hate crimes.

Jimmy Carter once said that America is not a melting pot, but a beautiful mosaic. We have all sorts of people here, but we want them to maintain their unique identities, not assimilate into some generic unity. However, this very characteristic that makes our nation so wonderful also provides the context for stigma, segregation, and hate crimes. We’ve come a long way in the past two centuries: from slavery to emancipation, segregation to civil rights. But de facto segregation still exists, and while it’s often about race, it’s also about poverty–and both race and poverty are often connected to health disparities.

Jimmy Carter once said that America is not a melting pot, but a beautiful mosaic. We have all sorts of people here, but we want them to maintain their unique identities, not assimilate into some generic unity. However, this very characteristic that makes our nation so wonderful also provides the context for stigma, segregation, and hate crimes. We’ve come a long way in the past two centuries: from slavery to emancipation, segregation to civil rights. But de facto segregation still exists, and while it’s often about race, it’s also about poverty–and both race and poverty are often connected to health disparities.

On the one hand, groups self-segregate for a variety of reasons, and it’s not entirely clear whether this is good or bad. Self-segregation may be about the joys and comforts of sharing a common culture or language, or it may be about banding together to survive oppression. The best thing I’ve come across on this topic is Beverly Daniel Tatum’s book Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?

On the other hand, we segregate in other important ways that seem not quite right. We have affluent neighborhoods and low-income neighborhoods and there are a host of institutional factors and personal behaviors that reinforce these divides. For example, although illegal, realtors often steer potential homebuyers away from certain “undesirable” neighborhoods. Banks follow questionable lending practices. Local governments zone industrial plants near housing projects. You get the idea.

Capitalizing on these patterns of residence, the political parties gerrymander districts that will help them win elections. Have you seen a map of North Carolina’s Congressional districts? Those long skinny districts and the highly irregular borders are not drawn for convenience; they demarcate the racial composition of the population across the state.

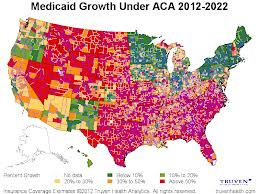

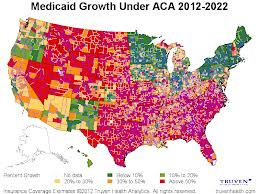

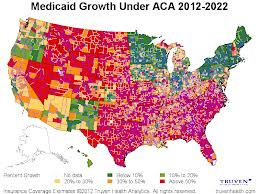

All of these are primarily local issues. They occur because of people’s inherent biases and, with the exception of gerrymandering, they are not established by laws or regulations. They are just the way society seems to work. But, knowingly or not, the Supreme Court’s decision to make the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion optional for states has created the opportunity for health disparities to be formalized into law, thanks to federalism and our country’s deep partisan divide.

It’s old news that only 26 of our 50 states have decided to expand the Medicaid program to all U.S. citizens residing in their state with incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level, but the expansion has only been a reality for 6 months. Now we are seeing how it is playing out on a personal level. One of the concerns among policymakers was that low-income people would emigrate from non-expansion states and flood into expansion states. A consensus is emerging that, while this may happen to some extent, it is unlikely to be a major issue–mostly because low-income people don’t have the resources to relocate.

What is particularly striking to look at are towns on either side of a state border. In some cases, single towns actually span state lines. And, if one state has expanded Medicaid, while the neighboring state hasn’t, whether or not a low-income person has health insurance may depend on what part of town they live in. Texarkana is one such town, and Annie Lowrey writes about this issue in the New York Times. Her point–and the one I am echoing here–is that we have formalized the unequal treatment of similarly situated persons based on nothing more than where they happen to hang their hat.

Somehow we tend to be okay with this unequal treatment when there’s enough of a buffer in place. For example, if the low-income in California are treated differently than the low-income in Indiana, we’re able to come up with reasons–real or imagined–that allow us to reconcile that to ourselves. But reduce the geographic distance, and focus on the unequal treatment that exists between residents of Chicago, Illinois and Gary, Indiana, and suddenly it gets much harder to ignore. We may all be different, and our differences may be part of what makes us beautiful as a nation, but we are all Americans. As such, it doesn’t seem right to deny some of us health insurance just because we don’t live in the right part of town.