Now we get to the biggest failure of them all — the individual mandate. The premise was simple: If people aren’t buying what they should (in this case, health insurance), pass a law telling them they have to, and they will. Presto, Change-o problem solved!

Now, to be fair, Congressional Democrats weren’t quite that simple minded. They threw in lots of subsidies and required that insurers enroll anyone who applied, no questions asked. So, they made it affordable and available, along with being mandated. So, it should work like a charm, right?

Now we get to the biggest failure of them all — the individual mandate. The premise was simple: If people aren’t buying what they should (in this case, health insurance), pass a law telling them they have to, and they will. Presto, Change-o problem solved!

Now, to be fair, Congressional Democrats weren’t quite that simple minded. They threw in lots of subsidies and required that insurers enroll anyone who applied, no questions asked. So, they made it affordable and available, along with being mandated. So, it should work like a charm, right?

Well, maybe in a vacuum. But in reality this rule is being inserted into a very complex and mature system of existing subsidies, responsibilities, and incentives. In this case, one of the primary factors is the role of employers in providing and paying for coverage.

Many people, including this writer, believe that placing that responsibility on employers was a major policy screw-up that created all the wrong dynamics in health care and virtually eliminated market functions because the payer and the consumer were not the same person.

Nevertheless, it is a system we have lived with for two-thirds of a century. Almost everything about health care and employment has been built around that relationship — prospective employees consider a company’s health benefits when deciding to take a new job; employers devote a lot of staff time and resources on choosing benefit programs; laws and regulations are written to ease the problems of interruption of benefits when people change jobs; courts are concerned that employers may not always fulfill their obligations to their workers. Not all employers provide benefits, but all feel an obligation and responsibility to do so, and the ones who don’t offer health benefits often feel conflicted about it.

Unwinding all this, even if desirable, is extremely complex and should take a very long transition period as we all learn new ways of doing things.

Enter ObamaCare. This law provides stark incentives for employers to get out of the business immediately. It even assuages any guilt feelings the employer might have by, first requiring that they continue to help pay for it, and next, by offering workers richer subsidies than the employer typically can. An employer will be able to save many thousands of dollars per worker by dropping coverage and sending employees to the Obama Exchange where they will get a choice of benefits plans and substantial subsidies if they make under 400% of the poverty level. Instead of paying, say, $10,000 per worker for coverage, now the employer can pay a simple $2,000 penalty and use the savings to give each worker a raise. Most employers will be able to save even more by reducing their HR departments, and they will be freed of complaints about any problems with the health plan they offer.

In February, 2011 McKinsey & Company did a large (1.329) survey of employers asking about their intentions with the Affordable Care Act and found that 30% said their company would “probably” or “definitely” drop coverage as a result. McKinsey is an extremely credible firm, but that didn’t stop supporters of ObamaCare from lambasting the survey because it was not consistent with other economic analyses. McKinsey had to issue a statement explaining it was not intended to be an economic analysis, it was an opinion survey. I would argue that such a survey is probably far more accurate than an economic analysis that must rely too much on assumptions. Indeed, it likely understated the situation. As employers learn more about the requirements of the new law they are more likely to run away from it.

We can’t know until it happens how many employers will drop coverage, but the 30% estimated by McKinsey may be the minimum. That could mean 50 million or more people who used to get employer coverage no longer will. For those employees this means:

- No more automatic enrollment going along with the job. People will have to take the initiative to find out about the Exchange.

- No more pure community rating of the employee share of premiums. The Exchange will vary premiums every year based on a person’s age.

- No more paycheck deductions of the employee share of premiums. People will have to make some kind of payment arrangement for their share of the premium.

- No more convenient and friendly HR Department people to answer questions. People will have to seek out an “Exchange navigator” to get their questions answered.

These employees are also likely to find at the Exchange:

- A clunky web site run by the state or federal government laying out the coverage options.

- Overpriced insurance options. (Because insurers can no longer ask medical questions, they will have no idea what kind of risks they are enrolling, or the premiums needed to cover those risks. They will err on the side of caution and charge higher premiums.)

- Confusion about how much they will be charged for their share of the premium. (They will be subsidized, but the amount of the subsidy will vary according to their age, income, geographic location, family size, and choice of plan.)

- Insurance plans that cover a bunch of stuff they don’t want or need.

- No reliable source of personalized information. (Ever tried to call the Medicare helpline?)

Finally, they will realize that they don’t need to go through all this. They can delay making a decision until they really need to get health care services:

- Exchange coverage is guaranteed to accept them at any time with no questions asked.

- They can save a whole lot of money by not paying premiums and using that money for more pressing needs.

- There is no meaningful penalty for failing to enroll. What penalty there is applies only to people who make enough money to pay income taxes, and it can be collected only by seizing whatever tax return is due the taxpayer. This can be easily avoided by upping deductions at the start of the year.

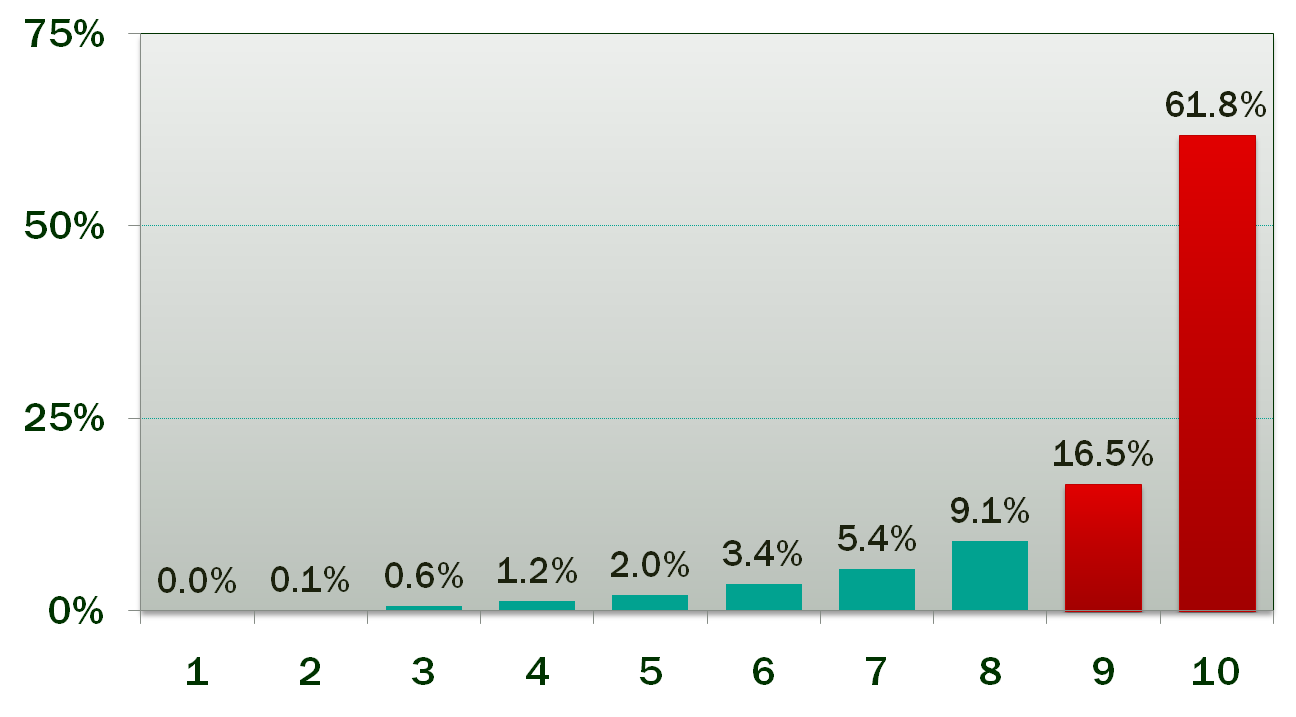

Most people have very few medical expenses in the course of a year. According to this chart 50% of the people in the United States consume only 3.9% of all health care expenses each year, while the top 20% consume 78.3%. People in the top 20% will certainly want to be covered but the bottom 50% get no advantage from insurance coverage. They spend far less on services than they would on insurance premiums.

Annual Spending as a Percent of the Total, by Decile

Source: Taken from “Medicare for All,” a presentation by Paul Y. Song, MD, PNHP 2011, slide #41; data attributed to Thorpe and Reinhardt.

Obviously not everyone will make the choice to go uninsured. People who are risk-adverse, or who have ongoing medical needs, or who have small children, will continue to be covered. But every year, every person will have to decide how best to spend their money. A very large number will decide they have better things to do with that money than spend it on insurance coverage they don’t want and never use.

The odds are that after all the trauma and expense of enacting and implementing ObamaCare, we will have fewer people insured than we did before it was enacted.