Originally published on MedCitynews.com.

Originally published on MedCitynews.com.

Originally published on MedCitynews.com.

Originally published on MedCitynews.com.

A closed-loop system of devices referred to as the artificial pancreas has been called the “holy grail” for Type 1 diabetes. Some scientists, though, think the future of diabetes treatment lies not in glucose meters and insulin pumps but in cell-based therapies with the potential to eliminate the need for daily insulin injections.

Islet cell transplantation is not a new concept, but patients receiving the experimental therapy up to this point have generally not sustained independence from insulin for more than a few years. Researchers and biotech companies are out are moving closer to changing that.

Type 1 diabetes develops when the beta cells in the pancreas can’t make insulin because the body’s immune cells attack and destroy them. Excess glucose builds up in the blood, requiring these people to take daily insulin injections to use up the glucose.

As a proposed solution to that, an islet cell transplantation takes islets — clusters of cells that contain beta and other kinds of glucose-regulating cells — from the pancreas of a deceased donor. After being purified and processed, those cells are implanted into the liver of a person with diabetes, where the beta cells begin to make and release insulin.

There are problems, though. Naturally, the immune system attacks what it recognizes as foreign, including transplanted islets. Immunosuppressive drugs can be used, but those introduce a host of other problems.

Then there’s the resources issue. According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, a patient typically needs to receive at least 10,000 islet “equivalents” per kilogram of body weight, and often require more than one transplant to reach insulin independence. That’s not scalable with a limited number of donors.

Sernova Corp. thinks it has the answers — or at least some of them. Ontario, Canada-based Sernova has been working with Dr. James Shapiro, a pioneer of the technique at University of Alberta at Edmonton, developing a two-pronged approach to helping the body regenerate beta cells.

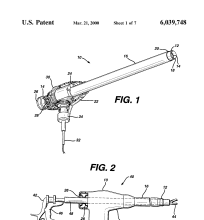

At the core of Sernova’s technology is a medical device. It’s a matchbook-sized, polymer pouch that’s implanted under the skin in the abdomen. It provides an “organ-like” environment to house islet cells.

“The device has multiple large pores in it that allow tissues to move into the device itself,” said CEO Dr. Philip Toleikis. “There are cylindrical plugs that tissue grows around, and when you pull the plugs out the micro-vessels grow in.”

People have been trying to make similar devices for 50 years, according to Dr. Rohit Kulkarni, principal investigator of islet cell and regenerative biology at Joslin Diabetes Center. The trick is making them out of materials that are porous enough to let glucose in and insulin out without letting immune cells in.

Toleikis said The Cell Pouch System was designed that way and has shown long-term efficacy in small animal models. “What we’ve found is a number of groups have tried to do this have made devices with smooth surfaces on the walls of the device,” Toleikis explained. “The body will treat that as a splinter — it will wall up and the device becomes not scalable.”

The second component to Sernova’s treatment is a proprietary cellular technology called Sertolin that’s mixed with donor cells to protect them from attack by immune cells. Ultimately, the goal is to eliminate the need for those costly and side-effect-causing immunosuppressive drugs.

That still leaves one gaping hole, though: the supply of islet cells to go into the pouch. The consensus seems to be that islet cells will eventually come from stem cells, but those techniques have not yet been perfected. “Those (approaches) are in place but have not been successful yet because efficiency has been so low,” Kulkarni said. “You start with a million cells but end up with 10 cells.”

That’s where other companies and organizations come in. Spring Point Project is one non-profit working to provide a “virtually unlimited supply” of pigs to serve as islet cell donors. Porcine cells, because of their wide availability and similarity to human cells, have in fact become a staple in most islet transplant approaches these days. For example, Islet Sciences in New York plans to submit an IND for its therapy – a combination of islets from young pigs and therapeutic agents that black the immune system’s rejection – to the FDA this year. Living Cell Technologies is conducting late-stage trials of its DIABECELL, also a porcine cell treatment, in Argentina.

While a fix for the supply problem is still a ways away, Sernova is pressing on. It initiated the first-in-human trial of the pouch in Canada one year ago. Shapiro is leading the Phase I/II clinical study of the safety and efficacy of the pouch in type 1 diabetes patients receiving islet cell transplants along with the standard anti-rejection medications.

“Once Dr. Shapiro gets comfortable with the procedures, we could potentially expand the clinical trial into the U.S. and Europe,” Toleikis said.

It’s also advancing Sertolin through pre-clinical trials with a $254,000 grant from the National Research Council of Canada. The goal is to find the ideal combination of islet cells and Sertolin, Toleikis said.

In addition to a potential new treatment for diabetes, Toleikis is excited about the potential of Sernova’s approach in treating other conditions, like hemophilia. “The cell pouch technology is a platform, so we can treat any kind of disease where there is a protein or hormone in short supply in the body,” he said. “We plan on expanding to work with companies that have therapeutic cells that need to be delivered somewhere in the body.”