“Confusion” and “Misunderstanding” are two of the words one can use to describe this passion-infused topic.

“Confusion” and “Misunderstanding” are two of the words one can use to describe this passion-infused topic.

“Confusion” and “Misunderstanding” are two of the words one can use to describe this passion-infused topic. Indeed, the whole subject of the cost of pharmaceutical and biotechnology products, including their management and administration, is very complex and almost incomprehensible. This article dissects some key aspects and tries to bring forward a broader perspective to the current debate.

“Confusion” and “Misunderstanding” are two of the words one can use to describe this passion-infused topic. Indeed, the whole subject of the cost of pharmaceutical and biotechnology products, including their management and administration, is very complex and almost incomprehensible. This article dissects some key aspects and tries to bring forward a broader perspective to the current debate.

Health spend in the US is the highest in the world – by almost any measure. The US spends over 17% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on healthcare, much more than any other country, including developed nations that have universal health coverage systems (Source: OECD Total Health Expenditure, 2012), and a sad reality is that our outcomes are not any better. Total costs grew at double-digit rates for a number of years, driven by increases in prices of products and related services, as well as by increased utilization from an aging population and the increasing prevalence of costly diseases. The good news is that, as reported by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, the growth rate in costs came down to about 4% in 2013, following a similar decline the year before (Update: They announced an increase of 11% in 2014, largely due to expansion in coverage). Even in the presence of heated politics, new legislation, better HealthIT capabilities, new compensation models that reward outcomes and not simply services, are all helping improve competitiveness and efficiencies; these are helping contain the growth in costs – while at the same time more people get at least some access to care. We have also seen over the last decade a decline in the rate of price growth of bio-pharmaceutical products in part due to increased competition, proliferation of generics, better targeting of therapies, and more aggressive contracting practices.

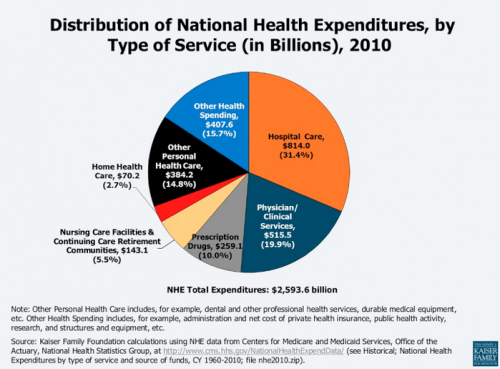

Let’s first understand the major components of health spend in the US. Below is a summary compiled by the Kaiser Family Foundation based on data from the Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services (Creative Commons license). There are various ways to analyze the data but the big takeaway – perhaps surprisingly – is that pharmaceutical care, or drugs, represents only 10% or 10 cents of each dollar spent on healthcare.

Second, and the focus of this article, it is important to understand that the terms “price”, “cost” and “value”, though often used interchangeably, actually mean very different things. There will be people who will debate these descriptions and definitions, as there isn’t a true consensus; but here’s my view of them.

The Price:

Generally speaking, this is the actual price of products as they are sold by the manufacturer. The whole subject of price calculations is complex and gets debated often, even in legal circles; however, in the simplest terms, it is a list or catalog or reference price – less any and all discounts and rebates (something often ignored in the debate). Basically, it represents the net dollars that the manufacturer receives. As will be evident after discussing the next two sections, manufacturers do not receive the whole of the 10% proportion of total healthcare. That 10% includes all kinds of post-manufacturer costs to the system that are not necessarily manufacturer income.

One implication of this is that even if biopharma companies were to cut their prices by something like a whopping 50%, the net overall effect would not be that dramatic given the small proportion that these costs represent overall.

Perhaps in a future installment of this column, we’ll discuss the drivers, rationale, and dynamics of the exit prices themselves.

The Cost:

In very simplistic terms, this is what someone actually pays for the product at the end of the line. It is akin to what you pay the supermarket for bananas vs. what the grower earned in the first place, with the difference being costs, mark-ups and fees that get added each step on their way to you.

Most products follow a supply chain path from manufacturer, to distributor, to retailer (such as a pharmacy), to patient (who may directly pay or whose plan may pay on their behalf) with each player in the chain paying a mark-up and various fees on top of the original net price. And then there are the patient co-pays. The sum total of each incremental mark-up and service can be significant for some products and can, once accumulated, sometimes double the original net price that the manufacturer gets.

Other products follow a slightly different path. In what is termed a “buy and bill” model, physicians, clinics and hospitals actually buy the product, usually from distributors, and then bill a payer (patient or insurer) once the product is dispensed or administered. Although the markups and fees are often controlled and regulated, and they include things like inventory and financing costs, they still add to the net price and contribute to the final cost.

Another part of the overall “cost” that gets borne by the end-payer, whether the patient or one’s medical or insurance plan, are the costs and ‘out-of-pockets’ that are part of the administration of that drug plan. This includes inventory, systems, formulary committees, distribution, mailing, counseling, professional fees, education, HealthIT, etc. etc. Of course, many of these are process-intensive and therefore are often subject to inefficiencies and waste.

Finally, another part of the cost is waste and abuse. This is a complex subject that we won’t have space to explore here, but there are other drivers in the system that dramatically increase the total cost of pharmaceutical care and are neither price-related, nor value-adding (see below). Examples are therapy duplications, non-compliance, product diversion, wrong therapy choices, and more.

The Value

Finally, this is the most complex, most esoteric and sometimes most controversial topic. The easiest way I have come to think about it is to contemplate what would be the consequences of not having or taking a particular drug, what is referred to as “the cost of the alternative” in health economics cicles.

For example, we all know that the system has paid billions of dollars over the years to cover statins, essentially drugs to lower bad cholesterol, as well as other products to lower high blood pressure, or products to thin blood in certain vascular conditions that require it. The clinical data on these products overwhelmingly points to dramatic reductions in the risk for heart attacks and strokes and their various complications including hospitalization and death; and the epidemiology backs it up with unequivocal large reductions in the population rates of hospitalizations or death from these conditions. So, one could estimate the cost or value to society of these benefits that, in part, must be attributed to pharmaceutical care. Another way of putting it is asking what would have been the economic and human costs had these products not been available.

There are many other examples, in many therapeutic areas where people are living longer and/or more comfortably and/or more productively.

Of course, there is another side to this coin. Sometimes drugs simply don’t work or happen to cause adverse events, sometimes serious or even fatal. I am optimistic that scientific research and drug development are progressing at such a pace that they are helping us better understand how biology and genetics work, and how to better select the right drug for the right patient for the right condition (personalized or precision medicine), and to find ways to reduce the negative aspects of that drug’s therapy. The better we can do this, the greater the final value of pharmaceutical care because we will end up more often wth the right product, for the right patient, at the right time.

As mentioned earlier, there are elements of “value-based payments” in the new health laws and health plans in the US and there have been efforts to establish “value-based contracting” for bio-pharmaceutical products, with payments no longer made simply for volume, but include some form of risk-sharing based on the actual benefits derived. The latter are in their infancy as the methodologies are very complex, but we’ll likely start to see an increase in these models, especially as other countries, such as Germany and the UK, go down this path. One of the impediments for progress in this area in the US is the patchwork of regulations and case law that, inadvertently, create all kinds of conflicts and barriers for innovative and more responsive pricing mechanisms; hopefully these will change to enable workable arrangements that, in the end, benefit patients.

In conclusion, indeed the system spends billions of dollars on bio-pharmaceutical care. The total cost of this care is about 10 cents of every healthcare dollar. This spend is for amazing tools that are helping the medical profession every day keep people suffering less, stay out of hospitals, and live longer. Things are not perfect, every product doesn’t work for everyone who may need it; there is waste and abuse, people may be exposed to adverse events to one degree or another, and there are many process and economic efficiencies and improvements possible, but understanding these three concepts of price, cost and value can help everyone have a more informed discussion of this complex subject. Only addressing ex-manufacturer prices, even aggressively, will not make as big a difference as the headlines suggest.

_3.jpg)